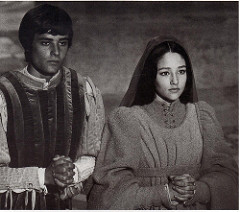

There was a period of time (freshman year honors English) when after reading a classic piece of literature, my class was guaranteed to watch a film adaptation of it. It happened for Great Expectations, and, inevitably, it happened for Romeo + Juliet. The divide between me and some of my acquaintances came here: while some classes watched the period-accurate film from the ‘60s, the one with that actor that looked unnervingly like Zac Efron, my class and a couple others watched the color-blown, musically rich, tooth-achingly delicious 1996 Baz Luhrmann version.

If you can’t tell, I have a soft spot for it.

There’s got to be approximately 6,017 reviews of the film online, so fear not, this isn’t another one. What I’m reminiscing on today are a few casting and character choices I loved—maybe a few I didn’t. After all, that’s been my mission here so far, hasn’t it?

Let’s start with something I mentioned very fleetingly a long time ago. Once upon a time, I mentioned that Romeo and Juliet can be approached from a racial perspective. This is, indeed, one of my favorite variations to impose on the play. Luhrmann’s film gives that a nod—in a bit of a convoluted way, maybe, but there nonetheless. Throughout the film, we see marked Latinx influences in the Capulet family, juxtaposed by the Montagues’ touristy Hawaiian shirts:

- The Nurse is played as the trope of the Latina housekeeper/nanny (and played by a white British actress, oops)

- Tybalt is played by Colombian-American John Leguizamo (caving to the stereotype of the quick-tempered fighting Latino? Maybe)

- Even Juliet’s father (again, a white actor) is given a bit of an ethnic twist

But most remarkably in my mind, the iconography of Latino Catholicism is rampant. Candles, candles, candles. Rosary beads. With the film filmed majorly in Mexico City, and set in a Miami lookalike, the racial identity of the Capulets isn’t hard to miss. Was the execution flawless? Of course not; as I alluded to, there’s plenty to criticize. But it’s a nice, realistic touch to something that could have easily been made a snow-white fantasy.

As long as we’re talking race, we have to talk about one of my hands-down favorite parts of the film: Harold Perrineau’s standout Mercutio. Dear God. That interpretation may have changed my life. While reading the play, we had commented extensively on Mercutio’s bold, flamboyant nature—Mercutio even more than Romeo would be the character most likely to do just about anything. When Luhrmann made this include a drag number, everything clicked like clockwork in my head. Mercutio is black—he is different from either side of the feud. He does drag—because why the hell shouldn’t he? This is even before we talk about Perrineau’s excellent acting. Mercutio is the golden god of the film, an example of Luhrmann’s ability to craft a true-to-text character that resonates with the modern. Which is why I get upset, every time, that after his death, his best friends simply abandon his body on the beach. It’s infuriating to make a character that richly nuanced and then toss him aside like a set piece.

If only the play was as peppy and happy as this video, via Ariel Gomez Ponce.

Which leads me to the growl-inducing anger I feel when I think about Dash Mihok’s Benvolio. You shouldn’t screw up any character in Romeo and Juliet, but in my opinion, you particularly shouldn’t screw up Benvolio and Mercutio. They are the benchmarks by which we measure Romeo’s behavior. They provide emotional context—does he always act like this? How do ensemble characters feel about this main character? These are things the best friends provide for us. Note: best friends. The boys are supposed to be peas in a pod, by God. Particularly with Benvolio, the lone survivor of his peers, you need to communicate that friendship, those relationships outside of Juliet. And yet. Talk about characters being set pieces—Mihok’s Benvolio does it to a tee. I could strangle Luhrmann for thinking that what the ensemble needed was a dumb brute character when Benvolio is anything but. My anger peaks at Mercutio’s death. Benvolio seems surprised, stunned a little, but not terribly involved. Not very best-friend-like. Oh, my fury.

Even after heavy reflection, I still love that darned movie. It feels true to the Romeo and Juliet experience. Latinx Capulets? Cool! Could have been done better. Black cross-dressing Mercutio? Beyond excellent! Give him more respect! Dunce Benvolio with that stupid buzzcut? …We don’t have to talk about it. Learn and move on. All in all, to touch the tip of the iceberg, the film did the play a great service in making the character choices seem realistic and accessible. Perfect? No. A jumping off point? Definitely.